- Home

- Propositions

- Candidates

- Quick-Reference Guide

- Voter Information

- Political Parties

- Audio/Large Print

California Statewide Direct Primary Election Tuesday, June 3, 2014

Official Voter Information Guide

Overview of State Bond Debt

Prepared by the Legislative Analyst's Office

This section describes the state's bond debt. It also discusses how Proposition 41—the $600 million veterans housing bond proposal—would affect state bond costs.

Background

What Are Bonds? Bonds are a way that governments and companies borrow money. The state government, for example, uses bonds primarily to pay for the planning, construction, and renovation of infrastructure projects. The state sells bonds to investors to provide “up-front” funding for these projects and then commits to repay the investors, with interest, over a period of time.

What Do Bonds Fund and Why Are They Used? The state typically uses bonds to fund public infrastructure projects such as roads, educational facilities, prisons, parks, water projects, and office buildings. Bonds have also been used to help finance certain private infrastructure, such as hospitals and housing for veterans. A main reason for issuing bonds is that infrastructure typically provides services over many years. Thus, it is reasonable for current, as well as future, taxpayers to help pay for them. Additionally, the large costs of these projects can be difficult to pay for all at once.

What Types of Bonds Does the State Sell? The state sells several major types of bonds. These are:

- General Obligation Bonds. Most of these bonds are paid off directly from the state's General Fund. The General Fund is the state's main operating account, which it uses to pay for public schools, higher education, prisons, health care, and other services. An example of general obligation bonds would be the statewide bonds for local school district facilities. Some general obligation bonds, however, are paid from designated revenue sources, with the General Fund only providing back-up support in the event the designated revenues fall short. For example, the state repays some past water bonds using funds from agencies that receive water from the bond-funded projects. General obligation bonds must be approved by the voters and their repayment is guaranteed by the state's general taxing power.

- Lease-Revenue Bonds. These bonds are paid off from lease payments (primarily from the General Fund) by state agencies using the facilities the bonds finance. These bonds do not require voter approval and are not guaranteed by the state's general taxing power. As a result, they have somewhat higher interest costs than general obligation bonds.

- Traditional Revenue Bonds. These bonds also finance infrastructure projects but are not supported by the General Fund. Rather, they are paid off from a designated revenue stream generated by the projects they finance—such as bridge tolls. These bonds also are not guaranteed by the state's general taxing power and do not require voter approval.

After selling bonds, the state makes annual principal and interest payments until the bonds are paid off. Generally, investors do not pay state and federal income taxes on bonds issued by the state. This allows the state to sell bonds at lower interest rates, which results in lower state debt payments. However, in some cases, the state sells bonds that do not qualify for the federal tax exemption. For example, historically, many housing-related bonds have not received a federal tax exemption.

What Are the Costs of Bond Financing? The annual cost of repaying bonds depends primarily on the interest rate and the time period over which the bonds have to be repaid. The state usually makes bond payments over a 30-year period (similar to payments homeowners would make on most 30-year fixed-rate mortgages). Assuming an interest rate of 5 percent, for each $1 borrowed, the state would pay close to $2 over a typical 30-year repayment period. Of that $2, roughly $1 would go toward repaying the amount borrowed and close to $1 for interest. However, because the repayment for each bond is spread over the entire 30-year period, the cost after adjusting for inflation is less—about $1.30 for each $1 borrowed. When the state issues taxable bonds, it often issues them with a shorter repayment period—for example, ten years. A shorter repayment period results in higher annual payments, but lower overall interest costs and thus lower total repayment costs.

Infrastructure Bonds and the State Budget

Amount of General Fund Debt. The state has about $85 billion of General Fund-supported infrastructure bonds outstanding—that is, bonds on which it is making principal and interest payments. This consists of about $75 billion of general obligation bonds and $10 billion of lease-revenue bonds. In addition, the voters and the Legislature have approved about $33 billion of authorized general obligation and lease-revenue infrastructure bonds that have not yet been sold. Most of these bonds are expected to be sold in the coming years as additional projects need funding.

General Fund Debt Payments. In 2013–14, the General Fund's infrastructure bond repayments are expected to total over $5 billion. As previously authorized but currently unsold bonds are marketed, outstanding bond debt costs will rise, likely peaking at over $7 billion in 2019–20.

This Election's Impact on Debt Payments. The veterans housing bond proposal on this ballot (Proposition 41) would allow the state to borrow up to $600 million by selling general obligation bonds to investors. The average annual debt service on the bond would depend on the timing and conditions of its sales. However, assuming an interest rate of 5 percent, that the bonds would be issued over a five-year period, and that each bond would be repaid over ten years, the estimated annual General Fund cost would be about $50 million. In total, we estimate that the measure would require total debt-service payments of about $750 million over the 15-year period during which the bonds would be paid off.

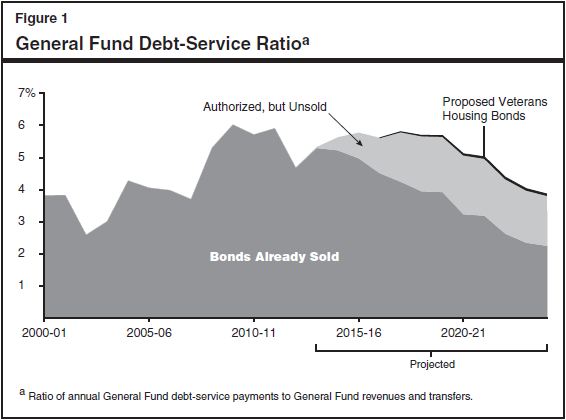

This Election's Impact on the Debt-Service Ratio. One indicator of the state's debt situation is its debt-service ratio (DSR). This ratio indicates the portion of the state's annual General Fund revenues that must be set aside for debt-service payments on infrastructure bonds and, therefore, are not available for other state programs. As shown in Figure 1, the DSR is now approaching 6 percent of annual General Fund revenues. If no additional bonds are approved by voters or the Legislature, the state's debt service on already authorized bonds is projected to peak at just under 6 percent of General Fund revenues in 2017–18, and decline thereafter.

If voters approve the proposed veterans housing bond on this ballot, it would increase the DSR by less than one-tenth of a percentage point. However, if voters approve additional bonds in elections after June 2014, future debt-service costs shown in Figure 1 would be higher. For example, at the time this analysis was prepared, a water bond was scheduled to be on the November 2014 ballot.